(I'm still editing and making changes to this document, but feel free to read; I hope it's useful to you!)

tl;dr: wrap your test interactions with act(() => ...). React will take care of the rest.

Note that for async act(...) you need React version at least v16.9.0-alpha.0.

Let's start with a simple component. It's contrived and doesn't do much, but is useful for this discussion.

function App() {

let [ctr, setCtr] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

setCtr(1);

}, []);

return ctr;

}So, it's an App with 2 hooks - a useState initialized with 0, and a useEffect which runs only once, setting this state to 1. We'll render it to a browser like so:

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById("app"));You run it, and you see 1 on your screen. This makes sense to you - the effect ran immediately, updated the state, and that rendered to your screen.

So you write a test for this behaviour, in everyone's favourite testing framework, jest:

it("should render 1", () => {

const el = document.createElement("div");

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("1"); // this fails!

});You run your tests, and oops 😣

That doesn't seem right. The value of el.innerHTML claims to 0. But how can that be? Does jest do something strange? Or are you just hallucinating? The docs for useEffect make this a bit clearer - "By using this Hook, you tell React that your component needs to do something after render". How did you never see 0 in the browser, if even for a single moment?

To understand this, let's talk a bit about how React works. Since the big fiber rewrite of yore, React doesn't just 'synchronously' render the whole UI everytime you poke at it. It divides its work into chunks (called, er, 'work' 🙄), and queues it up in a scheduler.

In the component above, there are a few pieces of 'work' that are apparent to us:

- the 'first' render where react outputs

0, - the bit where it runs the effect and sets state to

1 - the bit where it rerenders and outputs

1

We can now see the problem. We run our test at a point in time when react hasn't even finished updating the UI. You could hack around this:

- by using

useLayoutEffectinstead ofuseEffect: while this would pass the test, we've changed product behaviour for no good reason, and likely to its detriment. - by waiting for some time, like 100ms or so: this is pretty ick, and might not even work depending on your setup.

Neither of these solutions are satisfying; we can do much better. In 16.8.0, we introduced a new testing api act(...). It guarantees 2 things for any code run inside its scope:

- any state updates will be executed

- any enqueued effects will be executed

Further, React will warn you when you try to "set state" outside of the scope of an act(...) call. (ie - when you call the 2nd return value from a useState/useReducer hook)

Let's rewrite our test with this new api:

it("should render 1", () => {

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("1"); // this passes!

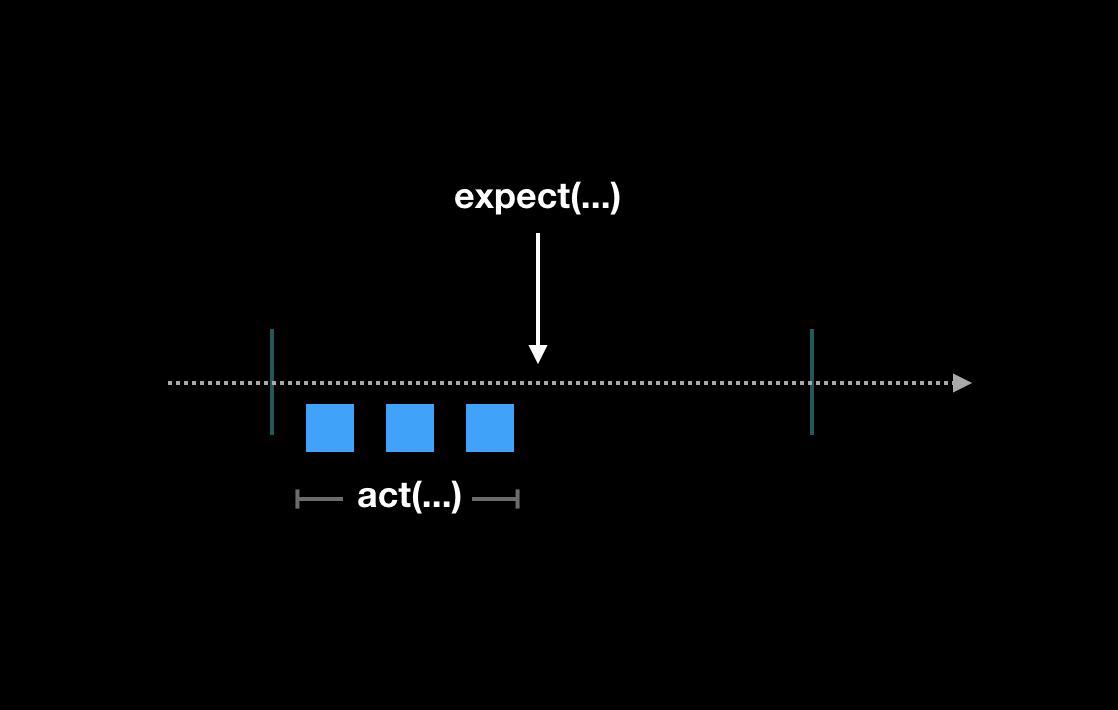

});Neat, the test now passes! In short, "act" is a way of putting 'boundaries' around those bits of your code that actually 'interact' with your React app - these could be user interactions, apis, custom event handlers and subscriptions firing; anything that looks like it 'changes' something in your ui. React will make sure your UI is updated as 'expected', so you can make assertions on it.

(You can even nest multiple calls to act, composing interactions across functions, but in most cases you wouldn't need more than 1-2 levels of nesting.)

Let's look at another example; this time, events:

function App() {

let [counter, setCounter] = useState(0);

return <button onClick={() => setCounter(counter + 1)}>{counter}</button>;

}Pretty simple, I think: A button that increments a counter. You render this to a browser like before.

So far, so good. Let's write a test for it.

it("should increment a counter", () => {

const el = document.createElement("div");

document.body.appendChild(el);

// we attach the element to document.body to ensure events work

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

const button = el.childNodes[0];

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

button.dispatchEvent(new MouseEvent("click", { bubbles: true }));

}

expect(button.innerHTML).toBe("3");

});This 'works' as expected. The warning doesn't fire for setStates called by 'real' event handlers, and for all intents and purposes this code is actually fine.

But you get suspicious, and because Sunil told you so, you extend the test a bit -

act(() => {

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

button.dispatchEvent(new MouseEvent("click", { bubbles: true }));

}

});

expect(button.innerHTML).toBe(3); // this fails, it's actually "1"!The test fails, and button.innerHTML claims to be "1"! Well shit, at first, this seems annoying. But act has uncovered a potential bug here - if the handlers are ever called close to each other, it's possible that the handler will use stale data and miss some increments. The 'fix' is simple - we rewrite with 'setState' call with the updater form ie - setCounter(x => x + 1), and the test passes. This demonstrates the value act brings to grouping and executing interactions together, resulting in more 'correct' code. Yay, thanks act!

Let's keep going. How about stuff based on timers? Let's write a component that 'ticks' after one second.

function App() {

const [ctr, setCtr] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

setTimeout(() => setCtr(1), 1000);

}, []);

return ctr;

}Let's write a test for this:

it("should tick to a new value", () => {

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("0");

// ???

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("1");

});What could we do here?

Option 1 - Let's lean on jest's timer mocks.

it("should tick to a new value", () => {

jest.useFakeTimers();

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("0");

jest.runAllTimers();

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("1");

});Better! We were able to convert asynchronous time to be synchronous and manageable. We also get the warning; when we ran runAllTimers(), the timeout in the component resolved, triggering the setState. Like the warning advises, we mark the boundaries of that action with act(...). Rewriting the test -

it("should tick to a new value", () => {

jest.useFakeTimers();

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("0");

act(() => {

jest.runAllTimers();

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("1");

});Test passes, no warnings, huzzah! Good stuff.

Option 2 - Alternately, let's say we wanted to use 'real' timers. This is a good time to introduce the asynchronous version of act. Introduced in 16.9.0-alpha.0, it lets you define an asynchronous boundary for act(). Rewriting the test from above -

it("should tick to a new value", async () => {

// a helper to use promises with timeouts

function sleep(period) {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, period));

}

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("0");

await act(async () => {

await sleep(1100); // wait *just* a little longer than the timeout in the component

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("1");

});Again, tests pass, no warnings. excellent!

This simplifies a lot of rough edges with testing asynchronous logic in components. You don't have to mess with fake timers or builds anymore, and can write tests more 'naturally'. As a bonus, it will (eventually) be compatible with concurrent mode!

While it's less restrictive than the synchronous version, it supports all its features, but in an async form. The api makes some effort to make sure you don't interleave these calls, maintaining a tree-like shape of interactions at all times.

Let's keep going. This time, let's use promises. Consider a component that fetches data with, er, fetch -

function App() {

let [data, setData] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

fetch("/some/url").then(setData);

}, []);

return data;

}Let's write a test again. This time, we'll mock fetch so we have control over when and how it responds:

it("should display fetched data", () => {

// a rather simple mock, you might use something more advanced for your needs

let resolve;

function fetch() {

return new Promise(_resolve => {

resolve = _resolve;

});

}

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("");

resolve(42);

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("42");

});The test passes, but we get the warning again. Like before, we wrap the bit that 'resolves' the promise with act(...)

// ...

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("");

await act(async () => {

resolve(42);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("42");

// ...This time, the test passes, and the warning's disappeared. Brilliant. Of note, even though it might appear like resolve(42) is synchronous, we use the async version to make sure microtasks are flushed before releasing scope, preventing the warning. Neat.

Now, let's do hard mode with async/await. :(

Haha, just joking, this is now as simple as the previous examples, now that we have the asynchronous version to capture the scope. Revisiting the component from the previous example -

function App() {

let [data, setData] = useState(null);

async function somethingAsync() {

// this time we use the await syntax

let response = await fetch("/some/url");

setData(response);

}

useEffect(() => {

somethingAsync();

}, []);

return data;

}And run the same test on it -

it("should display fetched data", async () => {

// a rather simple mock, you might use something more advanced for your needs

let resolve;

function fetch() {

return new Promise(_resolve => {

resolve = _resolve;

});

}

const el = document.createElement("div");

act(() => {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, el);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("");

await act(async () => {

resolve(42);

});

expect(el.innerHTML).toBe("42");

});Literally the same as the previous example. All good and green. Niceee.

Notes:

- if you're using

ReactTestRenderer, you should useReactTestRenderer.actinstead. - we can reduce some of the boilerplate associated with this by integrating

actdirectly with testing libraries; react-testing-library already wraps its helper functions by default with act, and I hope that enzyme, and others like it, will do the same.